# Dataflow Analysis

<!-- toc -->

If you work on the MIR, you will frequently come across various flavors of

[dataflow analysis][wiki]. `rustc` uses dataflow to find uninitialized

variables, determine what variables are live across a generator `yield`

statement, and compute which `Place`s are borrowed at a given point in the

control-flow graph. Dataflow analysis is a fundamental concept in modern

compilers, and knowledge of the subject will be helpful to prospective

contributors.

However, this documentation is not a general introduction to dataflow analysis.

It is merely a description of the framework used to define these analyses in

`rustc`. It assumes that the reader is familiar with the core ideas as well as

some basic terminology, such as "transfer function", "fixpoint" and "lattice".

If you're unfamiliar with these terms, or if you want a quick refresher,

[*Static Program Analysis*] by Anders Møller and Michael I. Schwartzbach is an

excellent, freely available textbook. For those who prefer audiovisual

learning, we previously recommended a series of short lectures

by the Goethe University Frankfurt on YouTube, but it has since been deleted.

See [this PR][pr-1295] for the context and [this comment][pr-1295-comment]

for the alternative lectures.

## Defining a Dataflow Analysis

A dataflow analysis is defined by the [`Analysis`] trait. In addition to the

type of the dataflow state, this trait defines the initial value of that state

at entry to each block, as well as the direction of the analysis, either

forward or backward. The domain of your dataflow analysis must be a [lattice][]

(strictly speaking a join-semilattice) with a well-behaved `join` operator. See

documentation for the [`lattice`] module, as well as the [`JoinSemiLattice`]

trait, for more information.

### Transfer Functions and Effects

The dataflow framework in `rustc` allows each statement (and terminator) inside

a basic block to define its own transfer function. For brevity, these

individual transfer functions are known as "effects". Each effect is applied

successively in dataflow order, and together they define the transfer function

for the entire basic block. It's also possible to define an effect for

particular outgoing edges of some terminators (e.g.

[`apply_call_return_effect`] for the `success` edge of a `Call`

terminator). Collectively, these are referred to as "per-edge effects".

### "Before" Effects

Observant readers of the documentation may notice that there are actually *two*

possible effects for each statement and terminator, the "before" effect and the

unprefixed (or "primary") effect. The "before" effects are applied immediately

before the unprefixed effect **regardless of the direction of the analysis**.

In other words, a backward analysis will apply the "before" effect and then the

"primary" effect when computing the transfer function for a basic block, just

like a forward analysis.

The vast majority of analyses should use only the unprefixed effects: Having

multiple effects for each statement makes it difficult for consumers to know

where they should be looking. However, the "before" variants can be useful in

some scenarios, such as when the effect of the right-hand side of an assignment

statement must be considered separately from the left-hand side.

### Convergence

Your analysis must converge to "fixpoint", otherwise it will run forever.

Converging to fixpoint is just another way of saying "reaching equilibrium".

In order to reach equilibrium, your analysis must obey some laws. One of the

laws it must obey is that the bottom value[^bottom-purpose] joined with some

other value equals the second value. Or, as an equation:

> *bottom* join *x* = *x*

Another law is that your analysis must have a "top value" such that

> *top* join *x* = *top*

Having a top value ensures that your semilattice has a finite height, and the

law state above ensures that once the dataflow state reaches top, it will no

longer change (the fixpoint will be top).

state. Each basic block's entry state is initialized to bottom before the

analysis starts.

## A Brief Example

This section provides a brief example of a simple data-flow analysis at a high

level. It doesn't explain everything you need to know, but hopefully it will

make the rest of this page clearer.

Let's say we want to do a simple analysis to find if `mem::transmute` may have

been called by a certain point in the program. Our analysis domain will just

be a `bool` that records whether `transmute` has been called so far. The bottom

value will be `false`, since by default `transmute` has not been called. The top

value will be `true`, since our analysis is done as soon as we determine that

`transmute` has been called. Our join operator will just be the boolean OR (`||`)

operator. We use OR and not AND because of this case:

```rust

# unsafe fn example(some_cond: bool) {

let x = if some_cond {

std::mem::transmute::<i32, u32>(0_i32) // transmute was called!

} else {

1_u32 // transmute was not called

};

// Has transmute been called by this point? We conservatively approximate that

// as yes, and that is why we use the OR operator.

println!("x: {}", x);

# }

```

## Inspecting the Results of a Dataflow Analysis

Once you have constructed an analysis, you must call `iterate_to_fixpoint`

which will return a `Results`, which contains the dataflow state at fixpoint

upon entry of each block. Once you have a `Results`, you can inspect the

dataflow state at fixpoint at any point in the CFG. If you only need the state

at a few locations (e.g., each `Drop` terminator) use a [`ResultsCursor`]. If

you need the state at *every* location, a [`ResultsVisitor`] will be more

efficient.

```text

Analysis

|

| iterate_to_fixpoint()

|

Results

/ \

into_results_cursor(…) / \ visit_with(…)

/ \

ResultsCursor ResultsVisitor

```

For example, the following code uses a [`ResultsVisitor`]...

```rust,ignore

// Assuming `MyVisitor` implements `ResultsVisitor<FlowState = MyAnalysis::Domain>`...

let mut my_visitor = MyVisitor::new();

// inspect the fixpoint state for every location within every block in RPO.

let results = MyAnalysis::new()

.iterate_to_fixpoint(tcx, body, None);

results.visit_with(body, &mut my_visitor);`

```

whereas this code uses [`ResultsCursor`]:

```rust,ignore

let mut results = MyAnalysis::new()

.iterate_to_fixpoint(tcx, body, None);

.into_results_cursor(body);

// Inspect the fixpoint state immediately before each `Drop` terminator.

for (bb, block) in body.basic_blocks().iter_enumerated() {

if let TerminatorKind::Drop { .. } = block.terminator().kind {

results.seek_before_primary_effect(body.terminator_loc(bb));

let state = results.get();

println!("state before drop: {:#?}", state);

}

}

```

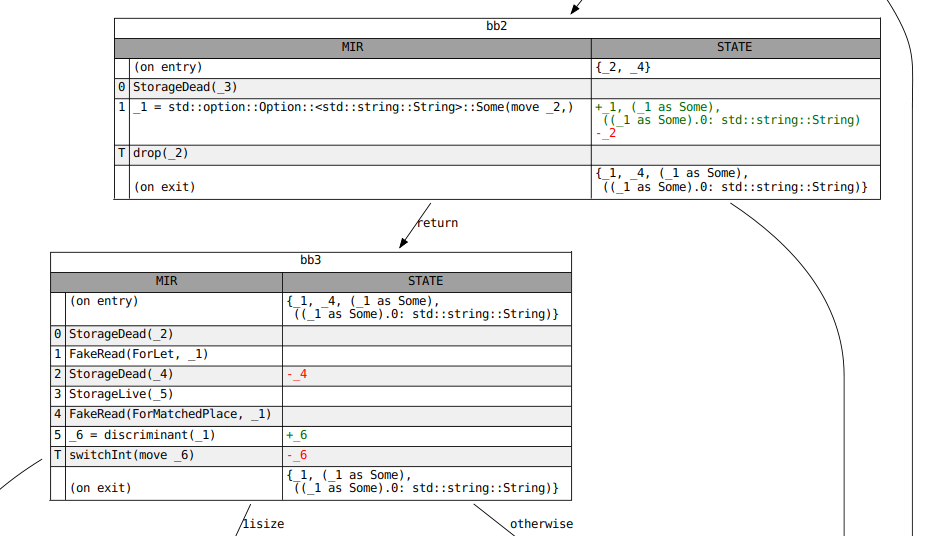

### Graphviz Diagrams

When the results of a dataflow analysis are not what you expect, it often helps

to visualize them. This can be done with the `-Z dump-mir` flags described in

[Debugging MIR]. Start with `-Z dump-mir=F -Z dump-mir-dataflow`, where `F` is

either "all" or the name of the MIR body you are interested in.

These `.dot` files will be saved in your `mir_dump` directory and will have the

[`NAME`] of the analysis (e.g. `maybe_inits`) as part of their filename. Each

visualization will display the full dataflow state at entry and exit of each

block, as well as any changes that occur in each statement and terminator. See

the example below: